WHY KYTHERA?

When Bev and I returned to Australia from our 1972/73 jaunt through Europe and the Middle East we moved to the small town of Bingara on the Gwydir River in northwest NSW to live. Bev took a teaching position at the local school. However after a year we found the town quiet as there was little to do other than go picnicking along the river or dig in old riverside rubbish dumps for old bottles.

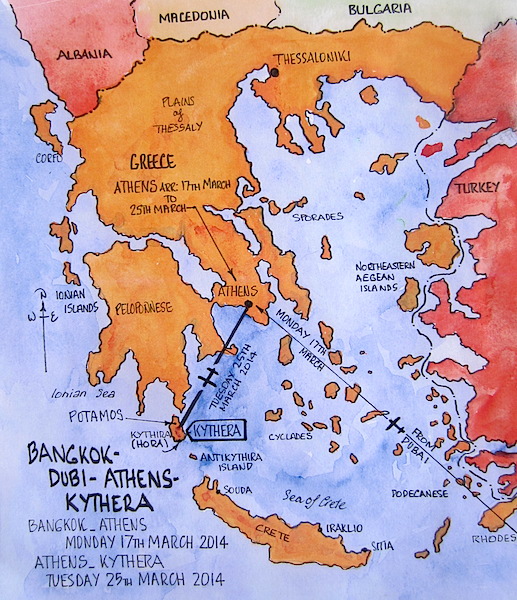

Moving to Tamworth about 90 kilometres south of Bingara we rented a house from an elderly Greek couple who had returned to Kythera, the island of birth, for a visit. Their son Alex and daughter-in-law Maria settled us in. Alex and Maria had two teenage daughters, Metaxia and Eirene and in latter years they used to babysit our two boys. Over the years Alex and Maria have urged us to go to Kythera, so in light of us deciding to continue our Encountering the Past Odyssey through Greece we thought, ‘why not?’ It would not be far out of the way.

Prior to setting off on this odyssey we visited Alex and Maria to learn more about Kythera and during our talk Alex began relating stories about his childhood on the island. I immediately decided that his story needed to be recorded so with the encouragement of his daughters I commenced to make a video film relating to Alex’s life.

The capital of Kythera is Chora/Hora. From Stavli to Potamos it is about 5km and from Potamos to Chora is 19 kms.

The Poulos family have a cottage on Kythera and it’s located in the mountainous region of Stavli. The cottage was built by Aleko’s grandfather in the 1930s and, fortunately for us, we are able to stay there. The only way to get around the island is by car, there is no public transport and the island is far too mountainous for us to consider using bicycles. I will devote a future post to the Stavli region and the cottage we are staying in. And now to the Aleko (Alex) story so far.

ALEKO GEORGOPOULOS (ALEX POULOS)

Aleko was born at home in the town of Potamos in 1929. His childhood was hard, as was the case with many Greek children at that time. In Aleko’s own words,it was ‘very very hard, very hard. Most of the time we had no shoes, our clothes were worn and it was hard to survive. My father, poor man, tried everything to make a living but he could not make ends meet’. However, he said that even though food was not plentiful there was always food on the table as there were olives, grapes, figs, almonds and edible wild plants growing on the island.

Alex and his younger brother Tzaneto (John) went to Potamos School, a short walk from home, but in winter with no shoes it was demanding to say the least. On a number of occasions they suffered severe chilblains. Aleko says he begged his mother to ‘get a knife and cut my toes off!

In high school years Aleko attended school in Chora but every Friday afternoon he and a mate used to walk back to Potamos and return on Sunday, a distance of nineteen kilometres. He says, ‘we used to walk barefooted over the stony road, hail, rain or shine, no coats, no nothing’. On enquiring why they subjected themselves to such hardship, he replied ‘to see the girlfriend’. Such is love! I believe he wanted to return home for the weekend.

Through the arch is the house in Potamos where Aleko was born and lived as a child. It has been recently sold and renovated.

In 1937 Aleko’s father, Peter, decided to emigrate to Tamworth, Australia, where an uncle had set up a fruit shop. He left his wife Metaxia and his two sons to follow once he had established himself in Australia. As often happens, the best-laid plans are often thwarted and in their case it was the invasion of the island during WW2, by the Italians and Germans. Once Kythera was occupied no one left the island, which meant Aleko’s mother and the two boys had to fend for themselves. Again, Aleko explained, ‘those years were very, very hard. I suspected from the expression on his face that those years were too emotionally difficult to talk about.

Aleko, mother Metaxia, brother Tzaneto (John) and Aleko’s father Panayiotis (Peter). This photograph was taken just prior to Peter leaving for Australia in 1937.

From left to right. Yiayia Stavroula (Aleko’s grandmother).

Metaxia, Aleko and Tzaneto. I do like the low camera angle.

The above photograph was taken on Kythera after Aleko’s father had left for Australia and prior to the occupation by the Italians and Germans.

Aleko recalled that during the war: ‘There was little food available other than what was growing on the island. Any extras we could only get on the black market. The drachma was useless, money was of no value. People would take a sack of drachma to the shop and all they could buy with it was a box of matches. Our needs were obtained by trading or by other means’. I was told that Aleko and a mate used to catch feral cats, prepare the carcasses and trade them with not only the locals in need of a little meat but with the occupying Italians as well. Revolting you might say, but perhaps we too would eat cats if we were driven to desperation.

Life on Kythera under Italian and German rule was not as fearsome as in other parts of Greece, however houses were looted and food, tools, hunting rifles and guns were confiscated. On the day when the German soldiers arrived in Potamos children were taken from the school and assembled in the town square where they witnessed the Germans machine gun the bank doors to gain access. Aleko, his mother and brother lived through these difficult years. In some way Kytherians were lucky as there was no industrial activity on the island and therefore little bombing occurred as compared to what happened to industrial port towns on the mainland, they were bespoiled completely. The only bombing on Kythera was just prior to German landings.

From what I can gather there were no mass executions on Kythera but as Aleko said, ‘on the mainland if the resistance fighters killed one German fifty Greek people would be executed’.

On the mainland, Greek people were subjected to unbelievable atrocities at the hands Axis members such as Bulgaria and, as quoted in Sacrifice of Greece in the Second World War’ (ISBN 978 960-475-995-8), ‘Bulgarians at both official and civilian levels did all they could to lessen the Greek population by massacres, murders, hangings and systematic starvation. They killed in every town of the zone they occupied. Seven thousand people were slaughtered in one night in the region of Drama. Albanians also committed atrocities under the protection of the Italians and Germans’. It should be noted that the Allies also caused mayhem in Greece in their attempts to rid Greece of the Axis powers; they extensively bombed port cities where the occupying forces were entrenched.

Aleko told me that during the occupation there was only one shortwave radio on the island and that was in the hands of a local priest. He said the priest would tune to the BBC and if it was good news on the war front he passed word around the island by a special sequence of church bell rings. It was Aleko’s job to peel the bells. The islanders knew the secret code but not the occupying forces. This event was confirmed by a number of independent sources.

In the course of confirming some of Aleko’s stories I met with many Kytherians including priest Father Petros. When I asked about the bell ringing he confirmed that it did occur and a Greek historian in Piraeus, when I told him the story of the bells, said it was done not just on Kythera but in other parts of Greece as well.

The majority of the Germans occupying Kythera left at the time of the battle of Crete. During that battle Aleko said ‘the sun was blanked out by thousands of German aircraft flying over’. On the 20th May 1941 German forces launched an attack on Crete but Allied forces along with Cretan civilians managed to defend the island. However, due to a miscommunication and along with Allied commanders failing to assess the situation correctly, the island fell into German hands. The success of the Germans was attributed to the fact that thousands of airborne commandos were flown in and it was the aircraft carrying these commandos that Aleko saw flying over Kythera.

Eventually the Axis powers were defeated and during September 1944 the last of the Germans on Kythera left, leaving the locals to rebuild their lives. Aleko, his brother and mother had been separated from Peter for seven years when the Germans left.

During his secondary school years, Aleko worked for a bootmaker (his mother thought it would keep him out of mischief). There was no wage as the drachma still had very little value and the bootmaker couldn’t afford to pay him anyway. However he was acquiring new skills (the preparation of cats was not considered to have much of a future!) At 17 he was offered a job by another bootmaker and that was his first paying job. Aleko said, ‘I gave my first pay to my mother, she broke down and cried’. He was impressed by both bosses, describing them as ‘wonderful men, wonderful men’.

In 1947 Metaxia (Aleko’s mother) made plans to leave for Australia and join her husband Peter. The trio went to Athens to board a ship to the land of the Antipodeans but their plans were unrealised again. The immigration officer informed Aleko he could not leave the country because he was eighteen and of national service age. When Aleko told me this story he was, as most Greeks are, very expressive with his hands. He imitated his mother’s reaction: ‘My mother shouted, “What! what!” and threw her hands into the air’. The outcome was that he waved goodbye to his mother and brother and returned to Kythera to live with his Uncle Manolis and Aunty Katina until he could effect his departure to Australia. Aleko did not do national service, he managed to negotiate his way out which was a common practice at the time. Had he done service he said, ‘I would have been involved in a civil war where father killed son due to their political differences’.

NB: In 1973 Aleko and Maria and their girls visited Greece and on entry he was told that it would be necessary to pay the equivalent of $250 because he left the country not having done national service. The long arm of the Greek law caught up with him twenty-five years later!

After his mother left Aleko continued with his education knowing that one day he would join his parents and brother in Australia. After receiving a letter from his father in Australia indicating that his brother was doing well at school and the Australian people were very welcoming, Alex spoke with the headmaster of the school about going to Australia: ‘I have decided to go to Australia as I do not think this country has a future’, and the headmaster agreed.

In 1948 Aleko finally made the move when his father bought him a ticket from a Sydney Kytherian travel agent. He was one of a number of Kytherians who managed to board an ex-military DC3 aircraft bound for Sydney. It cost five hundred and ten pounds for the flight, a significant amount in 1948. When I spoke with him about the flight he waved his hand under the table, which I read as ‘a black market deal’. The flight took seven days, landing each night. There were no seats, they sat on the floor and there was no water or food. The first landfall in Australia was Darwin and when the local Greek community heard that a plane from Greece had arrived they welcomed the intrepid travellers with overwhelming enthusiasm.

The following photograph shows a street scene in Potamos at the time Aleko left for Australia. The men sitting outside the café would no doubt have been mates with him.

Relaxing after the war outside Livaditis Kafeneion (now Astikon) Potamos. It was in this café that the freedom fighters used to meet and discuss their plan of action. Copyright Emm.Sofios.

Fortunately for historians the late Kytherian photographer, Manoli Sofios, was dedicated to recording Kytherian history on film. The above photograph is one of his many photographs and it was supplied to me by his grand daughter, Evita, who is the proprietor of a photographic shop in Potamos.

The above photograph was shot through the doorway of the cafe from forty meters away using a 300mm lens, a very different set up than what Manoli Sofios would have used: he used a plate camera.

From Sydney Aleko flew to Tamworth, the fare was the equivalent of $2.50. The plane in which he flew was a wartime Avro Anson, which is now a museum piece at the Tamworth airport. At the airport his family was waiting for him: ‘in the doorway I saw my mother, brother and father. I didn’t know my father, I hadn’t seen him since 1937 when I was seven years old’.

Aleko settled into Tamworth well. He and his brother worked in the Royal Cafe their father had established. Leisure activities for Alex and his brother revolved mostly around playing soccer; they set up the first team in Tamworth.

The multinational soccer team in Tamworth. Aleko, second from right back row and his brother John on his left.

The intriguing thing about the team members in this photograph is that they were Greek, Dutch, South African, German and Italian. It’s interesting to note that a few years before, the Greek, German and Italian nations were fighting each other. Sport no doubt mends hostile bridges.

As happens with most blokes, they eventually marry. Aleko married Maria, a girl of Greek heritage born in Australia. He met Maria in a Greek café, of course, and says as soon as he set eyes on her he was captivated, ‘I asked her for a glass of water and when I finished it I asked for another then another so I could keep her in conversation. In those days it was not easy to see a girl alone and there was definitely no hanky panky!’ Both Maria and Alex became involved with community activities. They organised the first Greek ball in Tamworth: ‘four hundred people turned up, and the sprung floor of the town hall bounced up and down from all the Greek dancing. The next year, timber props were put under the floor to stop it collapsing’.

I asked Alex if he experienced any racism when he first went to Australia. He replied that Australians were helpful although ‘they used to call us bloody dagos’.

There are a number of explanations as to where the word ‘dago’ is derived. One reference says it comes from the Spanish name ‘Diego’, which means ‘James’. Originally coined in the 17th century by British sailors, it was used to indicate Spanish or Portuguese people, especially sailors. Despite the Hispanic origin of the word, in the 19th century the word ‘dago’ became more commonly used in the USA as a derogatory term for Italians.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s I lived in an inner suburb of Sydney and a lane ran along the rear of our house in which residents placed their garbage for collection by the ‘garbo man’. It was easy to tell which house Greek immigrants had moved into, it was the ones where olive oil tins were put out for collection. There are around 60,000 Kytherian descendants in Australia and I bet some of their parents lived in houses near where I lived as a child.

Alex and Maria have returned to Kythera a number of times over the years and what astonishes me is just how many people know them. We have also learned during our time here that Aleko’s story is one of hundreds of similar stories. He says, and it probably rings true for all Kytherians living in Australia, ‘Greece is my country but Australia is my home’ and he is adamant that he wants ‘to be buried in Tamworth’.

As I mentioned, Aleko and Maria have two daughters. Metaxia lives in Athens and on Kythera and Eirine lives in Brisbane. Metaxia has a son Alexander who is moving along the road of enrichment and he would not have been able to do this if it wasn’t for the hardships endured by generations of Greeks before him. I had it said to me whilst on Kythera, ‘All Greeks want to be heroes’. I think they are already heroes in light of what they have had to endure and especially now during the present financial crisis and to use a phrase coined by broadcaster Phillip Adams, ‘with colloquial ambiguity, I dips me lid”.

The next posting will be more of Kythera. Hope you stay with us as we explore this beautiful island.

Leaving a comment is no mystery, it is a little like travelling, ‘Just do it’.

Thanks for posting this story. My Kytherian grandfather Nicholas KASIMATIS emigrated to Australia in 1908 aboard the GMS Roon via Port Said, Egypt. He lived in Sydney in the Haymarket but left for San Francisco CA USA in 1912 aboard the RMS Moana Using the name George Milos. Such a small island but influenced my grandfather and father so much. Great to read this story about Kythera to understand what life was like. I was lucky enough to visit Kythera in 2017 meeting so many friendly Kasimatis’ and others and seeing the natural beauty of the island. I will never forget the smell of wild thyme and oregano as we landed in the late afternoon.

HELLO MARK

Thanyou for the comment re Kytheria. There is no doubt once you visit Kythera you always have the urge to go back. Bev and I remember the wild flowers and herbs too, there was one particular one which smelled beautiful but we couldn’t find the plant, I think there is an image on the blog of me sniffing plants.

Fred and Bev

Loved this story.

Aimee

Thanks for your comment. Sorry we couldn’t spend more time together when in Bangkok.

Fred and Bev

Hi Fred and Bev.

Wow I came across your story after doing some web surfing about Tamworth’s history. What a great story. Just recently a couple of Tamworth ladies started a Facebook page called “Tamworth Memories’ and the amount of information/history/stories told and added is amazing. There are now over 6,000 people who have visited/commented/added to the page.

Your story here about the Poluos family is amazing and very much part of Tamworths History in particular that Alex and his brother got the first Tamworth soccer team together. Do I have permission to use the soccer team photo on the page and link it back to this site so that people can read the story.

Regards

Brian Mitchell

Here is a link to the page…..

https://www.facebook.com/groups/676637399069346/

Dear Brian

Sorry for the delay in replying to you request but I had to contact Aleko’s daughter re your request. Bev will send you an email under separate cover advising additional info. There is no problem just is there is more information available. Thanks for your interest in our travels. You may link tBear with the history blog no worries. We are in Prague Czech Republic at the moment. Regards Fred and Bev

You certainly are a talented storyteller, Fred. Hope you get around to that book. Meanwhile the blogs will do! Keep on enjoying your adventures. Love Sue Bowe

Sue and Kevin the tropic birds not Umina ones.

Good to hear from you and pleased you are enjoying Tbearstravels. Bev and I in Thrace (over Turkey way and below Bulgaria) at the moment. Tonight we were going to put our little tent up in a slate quarry but it started to rain so we headed into a small town west of Kavala and moved into a hotel. Tomorrow we heading for Drama a town with much history. The writing of the blog doubles our time but I don’t suppose that is all so bad. Heading for Switzerland next week.

Fred and Bev

Hi Fred and Bev, I heard on the radio recently a Greek Museum has just opened in the Roxy Theatre in Bingara. Kythera featured in quite a few of the interviews.

We enjoyed your interview and it’s so important not to lose these stories. Cheers L&J

John and Leonie Yes we know about the Greek Museum in Bingara and what it entails. I may do a story about how it came about as many people on Kytheria told me about it.

Take care Fred and Bev

Great story Fred very inspiring! We sure do it easy these days!

Dear Sara There are hundreds of such stories out there but unfortunately the pages of history are being closed as the old timers pass on. I left with a number of Kytherians a questionnaires asking them to record their lives and if they do I might write a book about their lives. So much to do and so little time! Fred and Bev

Hi Fred a heartfelt thank you for writing dads story, whilst reading this post I have been overwhelmed with emotion. Enjoy our beautiful country and I wish I could share an ouzo and calamari with you at Our favourite ouzeri Cuckoo overlooking Kapsali love to you and Bev from Eirene at Caloundra xo

Eirene Glad you enjoyed your dads story, it was a pleasure to research and write. It gave Bev and I a purpose for visiting Kythera. Thanks to the Poulos mob for the hospitality and allowing us to stay in the Stavli cottage. I will be posting Stavli story soon so stay tuned. Fred and Bev

Ps Your father has a lot more to tell too, I will have another go st him when we return to Australia.